What is Treatment of adhesions after surgery?

In practice, it looks like this: in places where the serous membrane is damaged, collagen and elastic fibers and connective tissue cells are intensively produced. If at this time any internal organ (for example, a loop of intestine) touches the area of the damaged serosa, it is involuntarily involved in this process. A cord of connective tissue is formed, which leads from the wall of the internal organs to the inner surface of the abdominal wall. This is called adhesions.

Adhesions can also connect internal organs to each other. Each of them is also covered by a serous membrane. During the operation, micro-tears are not excluded. And these places of microtrauma can also subsequently become a source of the formation of adhesions between this organ and the organs adjacent to it.

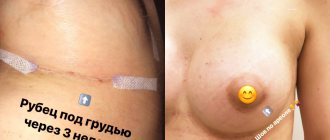

Also, at the site of contact and healing of tissues after their dissection or rupture, a scar may form, in which the normal tissue is replaced by a more rigid and inelastic connective tissue. Scars can be on the skin, or they can be on internal organs.

Classification of postoperative sutures

How quickly the sutures heal after surgery largely depends on the nature of their application and the materials used. In this regard, post-surgical procedures are usually classified as follows.

- Bloodless (the edges of the wound are glued together with a special plaster) and bloody (a classic suture that is applied manually with a medical instrument). In turn, the latter are divided into:

- simple knots (applied at a distance of 1–2 cm from each other, after which the knot is tightened until the edges of the incision touch);

- intradermal continuous (considered the most effective, since after their healing there are no traces left);

- mattress (applied after abdominal surgery);

- purse string (used in plastic surgery, as well as in operations to reduce the volume of the stomach);

- entwining (circular sutures that are used to sew together blood vessels and hollow organs).

- Manual (applied with a needle, thread and other special tools) and mechanical (performed with a medical stapler).

- Submersible (applied during operations on internal organs with threads that are absorbable or implanted into living tissue) and removable (they are used to stitch the skin, and after the edges of the wound have fused, the threads are removed).

Absorbable sutures are made in cases where long-term fixation of the edges of the incision is required, for example, when cutting the uterus during a cesarean section. As a rule, they are performed with threads from purified connective tissue, which is subsequently rejected into the organ cavity. To apply removable sutures, threads and other fasteners made of cotton, silk, metal and other non-absorbable materials are used (more than 30 varieties in total).

Hand stitching tools

How are adhesions treated?

According to the timing of formation of adhesions, they are distinguished:

- 7-14 days after surgery – the phase of young adhesions, when the adhesions are still very loose and easily torn;

- 14-30 days after surgery is the phase of mature adhesions, when the adhesions thicken and become strong.

Starting from the 30th day after the operation and further, for several years, the process of restructuring and formation of scars and adhesions occurs. The process is individual, much depends on the properties of the organism itself, its anatomical structure, and the functioning of internal organs.

The doctor may suspect the presence of adhesions in the abdominal cavity based on clinical data, medical history, and the results of studies such as ultrasound, CT, and colonoscopy. Adhesions in the abdominal cavity and pelvic cavity can be treated with medication or surgery. During surgery, the adhesions are separated, but this method should be used only in extreme cases, if the cords are so thick and rough that they severely disrupt the function of the organ, and more loyal and gentle treatment does not help.

How to care for the suture after surgery?

Once the edges of the incision tighten, there will be no need for additional support. Removal of sutures in the head, face and neck area occurs already on the 5th day after the operation. If they were applied in the area of the torso or limbs, then it will take at least 10 days for the wound to heal. Daily dressings are necessary for the first few days. The patient usually spends this time in the hospital. After discharge, tight bandages are usually no longer needed. But if necessary, you can always change the dressing at the nearest hospital or medical center.

Caring for the suture after surgery consists of daily treating the incision area with an antiseptic and taking medications that accelerate tissue regeneration. All medications for home therapy are used strictly according to the doctor’s recommendation!

Treatment of sutures is usually carried out with ready-made pharmaceutical preparations or homemade antiseptics, such as solutions of iodine, potassium permanganate, brilliant green or hydrogen peroxide. To avoid getting a chemical burn when performing such procedures, the liquid for disinfection should be prepared only according to a prescription issued by a doctor.

To speed up regeneration processes, external agents with wound healing and antibacterial effects are used. These include balsamic liniment (better known as Vishnevsky ointment), levomekol, ichthyol ointment and many others.

Pain of varying intensity after surgery is absolutely normal. If discomfort is severe, analgesics approved by your physician may be used.

Symptoms

The first clinical manifestations of the inflammatory process are observed several days after the operation. They manifest themselves in the form of swelling and hyperemia of the wound, and there are complaints of increasing pain. During palpation of the suture, the surgeon discovers a compaction without clearly defined boundaries. Purulent inflammation is accompanied by the release of a characteristic fluid - exudate.

After 1-2 days, additional symptoms appear:

- muscle pain;

- intoxication;

- increased body temperature;

- weakness and nausea.

An anaerobic infection develops much more rapidly and can lead to sepsis within two days after surgery without timely treatment.

Additional recommendations for suture care after surgery

In addition to medical procedures, certain lifestyle adjustments are also necessary in the postoperative period. In particular, the following rules must be adhered to:

- Limit physical activity. Any high and medium intensity exercise (running, aerobics, etc.) during this period is strictly contraindicated.

- Avoid heavy lifting. As a rule, a person who has undergone surgery should not lift more than 2–2.5 kg. This rule is especially relevant when caring for a suture on the abdomen after surgery.

- Limit mobility in the waist area (avoid sharp and high-amplitude bends and turns of the body) after abdominal surgery.

- Carry out water procedures with great care. Before the stitches are removed, or better yet, before a scar forms, it is strongly recommended not to wet the wound.

- Avoid any pressure on the wound. When it comes to how to care for a suture after surgery, this is one of the main rules.

- In cases where surgery was performed on an arm or leg, the injured limb should be placed above the level of the heart (for example, placed on a pillow) during sleep. If the wound is above the level of the neck, then it is better to sleep with the head of the bed raised by 45° (two pillows are enough for this).

- During abdominal operations, observe bed rest until the doctor allows you to break it. To avoid bedsores and improve blood circulation, you can perform simple movements such as lifting your limbs and performing light self-massage.

- Strictly follow the diet prescribed by your doctor (especially after abdominal surgery).

- Protect the wound from exposure to direct sunlight. After the tissue has healed and until a full-fledged skin forms in this area, you can use sunscreen.

What causes appendicitis?

Appendicitis is an inflammation of the vermiform appendix of the cecum, the appendix. The function of the appendix in the body has not been fully established. It is rather a vestigial organ. It is assumed that in the course of human evolution it has lost its main digestive function and today plays a secondary role:

- contains a large number of lymphoid formations, which means it partially provides immunity;

- produces amylase and lipase, which means it performs a secretory function;

- produces hormones that provide peristalsis, and therefore is akin to hormonal glands.

The causes of appendicitis are described by several theories:

- the mechanical one states that the reason for the development of appendicitis is obstruction of the lumen of the appendix with fecal stones or lymphoid follicles against the background of activation of the intestinal flora; as a result, mucus accumulates in the lumen, microorganisms multiply, the mucous membrane of the appendix becomes inflamed, then vascular thrombosis and necrosis of the walls of the appendix directly occur;

- the infectious theory is based on the fact that inflammation of the appendix is caused by an aggressive effect on the appendix of infectious agents localized here; usually this is typhoid fever, yersiniosis, tuberculosis, parasitic infections, amebiasis, but specific flora has not yet been identified;

- the vascular theory explains the development of appendicitis by a disorder of the blood supply to this part of the digestive tract, which is possible, for example, against the background of systemic vasculitis;

- endocrine The basis for the occurrence of appendicitis is the effect of serotonin, a hormone produced by multiple cells of the diffuse endocrine system located in the appendix and acting as a mediator of inflammation.

Appendicitis often develops against the background of other disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. A high risk of appendicitis is assessed for those individuals who are diagnosed with:

- chronic forms: colitis,

- cholecystitis,

- enteritis,

- adnexitis

Appendicitis most often develops between the ages of 20 and 40; Women suffer from it more often than men. Appendicitis ranks first among surgical diseases of the abdominal organs.

Prevention of appendicitis consists of eliminating negative factors, treating chronic diseases of the abdominal organs, eliminating constipation and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. The diet should include a sufficient amount of plant fiber, since it is this that stimulates intestinal motility, has a laxative effect and reduces the passage time of intestinal contents.

In what cases should you consult a doctor?

Seeking help from a doctor during the healing process of a suture is a completely normal practice, even in the absence of serious problems. And in the event of adverse reactions due to a violation of the treatment regimen or any unforeseen circumstances, it is absolutely impossible to delay it. First of all, it is dangerous to ignore the following symptoms:

- bleeding that cannot be stopped by conventional means;

- high temperature (more than 38 degrees);

- weakness, chills;

- increasing pain or other progressive discomfort that cannot be relieved with medications;

- purulent discharge of a bright yellow or green color with a thick consistency and very often with an unpleasant odor;

- severe redness, swelling, or swelling in the wound area;

- the skin at the site of injury is hard and hot to the touch;

- the appearance of a rash or blisters;

- Suspicion of seam dehiscence.

Current issues

Most patients, after undergoing a laser mole removal procedure, observe some characteristic reactions of the body during the first two weeks, some of which are normal responses that are compensatory in nature. Let's consider several pressing issues regarding the consequences of removing nevi on the face and body.

Can cancer occur after mole removal? Skin cancer, or melanoma, usually develops as a consequence of the malignant transformation of a melanoma-prone mole. Moreover, if during the laser correction process the specialist incorrectly determined the required depth of the beam and did not completely remove the mole, the risk of developing melanoma increases.

After removal, a tubercle appeared. Despite the low-invasiveness of the technique, in the process of removing the nevus, healthy surrounding tissue remains, which will have to undergo the healing process of the wound surface that has formed in place of the mole. In this case, this zone can form a small tubercle, which will be covered with a dense crust in a few days. This is considered a normal reaction to manipulation.

Inflammation after removal of a birthmark. The inflammatory process after laser correction usually lasts for the first days, after which it goes away. If inflammatory signs persist for a long time, you must immediately contact the specialist who performed the procedure.

Can a scar or scar form after removal of a nevus? The formation of scars can only be observed in the case of forced premature removal of the protective crust from the wound surface.

The scar itches and hurts after mole removal. Itching, burning, peeling and redness around a mole after removal are characteristic symptoms of a burn, which can be caused by unprofessional work of a doctor. This unpleasant complication develops if the specialist incorrectly determined the depth of exposure and subjected healthy skin cells to laser burning.

How long does it take for a wound to heal after surgery?

The rate of healing of a postoperative wound depends on many conditions. Among them:

- age;

- body mass;

- state of immunity;

- state of the cardiovascular system.

On average, it takes about 3 months from the moment of surgery to the formation of a scar. Depending on the complexity of the operation and if there are complications, this period may last 12 months. Tissue regeneration takes place in 4 stages.

- Inflammation (5–7 days). The body's standard defense reaction to damage. During this period, there is an increased production of substances that stimulate blood clotting.

- Polyferation (from 10 days to 1 month). At this stage, the formation of young connective (granulation) tissue, penetrated by a dense network of microvessels, occurs. At first it is bright red in color and grainy in consistency, but as the wound heals it becomes pale and smooth, and its bleeding decreases.

- Epithelization (from 1 to 3 months). The connective tissue is finally formed. Skin begins to form at the site of the wound. The number of vessels decreases, a scar forms.

- Scar formation (from 3 to 12 months). Temporary vessels completely disappear. Fibers of collagen and elastin - elements of connective tissue - form the scar.

The problem of the occurrence of postoperative causalgia remains very relevant to this day and is far from being finally resolved. Causalgia (from the Greek causis - burning and algos - pain, literally - burning pain) is a painful condition accompanied by excruciating, unbearable pain, which is usually burning in nature and intensifies in attacks, occurs in the patient, usually after surgical treatment, in the area suturing the abdominal wall and/or in the area of integration and fixation of the implant after hernioplasty.

The patient has a sensation of scalding the affected area with boiling water, cauterizing it with a hot iron. Light touch and dry heat cause increased pain, even when applied outside the affected area. An attack of pain can be triggered by any sharp irritation (sound, light), emotions. In the affected area, vascular and trophic changes are noted: persistent redness of the skin, increased skin temperature, thinning, pigmentation, impaired growth of nails, hair, sweating, bone tissue atrophy.

In modern hernia surgery, the most effective methods of inguinal hernioplasty using synthetic implants (allogernioplasty, tension-free hernioplasty), the use of which prevents the main cause of relapses - tissue tension in the surgical area - and allows to reduce the frequency of recurrence of inguinal hernias to an average of 1-5% [ 12].

Randomized controlled clinical trials have clearly shown a dramatic reduction in recurrence rates compared with techniques using patients' own tissue for hernia repair. However, postoperative pain has been recognized as one of the main problems associated with the use of implants. According to both domestic and foreign authors, the incidence of causalgia ranges from 4 to 15% [3-5].

To study the phenomenon of causalgia after hernioplasty, J. Mazin [6] in 2011, as part of his study, performed a retrospective search of the literature from 1998 to 2011. The review included an analysis of various open and laparoscopic hernioplasty methods. Risk factors for the development of postoperative pain after hernia repair were identified: preoperative pain, choice of anesthesia, fear of pain, wound infections, bleeding, duration of surgery and surgeon experience. In addition, 3 distinct types of chronic postoperative pain have been identified. A common factor in each type of pain is the presence of mesh.

The first type is the most common - somatic or nociceptive pain. As a rule, the cause is a pathology preceding the operation. This may include injuries to ligaments and muscles, as well as an aggressive reaction to the appearance of a postoperative scar or to the implanted synthetic mesh implant.

The second type, neuropathic pain, involves direct nerve damage. Certain problems may arise during the operation, for example, when a nerve gets caught in a suture or is caught in a staple when fixing the mesh. As a rule, these are branches of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves, as well as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh.

The third type of chronic postoperative pain is visceral pain. In principle, the etiology of this pain may be of intestinal origin, but along with this, dysuria or difficulty urinating can also contribute to the occurrence of visceral pain. Other genitourinary problems, such as ejaculatory dysfunction (usually preceding surgery) and erectile dysfunction, may play a significant role in causing this type of pain. However, it should be borne in mind that erectile dysfunction cannot be caused directly by surgical treatment of an inguinal hernia. The nerves responsible for erectile dysfunction originate from the II through IV sacral nerve roots, and not through the sensory nerves going to the groin area. Thus, it is anatomically impossible to cause impotence through surgical treatment of inguinal hernias. Despite this, there have been many court cases in which a plaintiff who had undergone hernia repair accused the surgeon of causing impotence as a result of the operation [6].

As a result, chronic postoperative groin pain was defined as pain lasting more than 30 days and having a negative impact on the patient's daily activities. The term “mesh inguinodynia”, introduced by C. Heise and J. Starling in 1998 [7], referred to causalgia after hernioplasty. This term is also well described and discussed in 2002 by C. Courtney et al. [8]. 5506 patients operated on over a period of more than a year were studied.

All types of hernioplasty were included in the study. According to the results, 3% of their patients experienced severe pain after 3 months, 8% of patients required further surgery for various reasons, and 15% were referred to pain clinics. Chronic pain in these patients negatively affected walking, work, sleep, interpersonal relationships, and mood.

In general, pain of varying intensity is present in the groin area after herniotomy for varying periods of time. If the pain lasts longer than 3 months, it is classified as chronic. At 3 months after surgery, it can be assumed that most nociceptive pain signals coming from a normal healing wound are on the decline. Therefore, pain lasting longer than 3 months may indicate a pathological prolongation of the nociceptive pain response or inflammation of some nerve. Although most patients who undergo hernia repair experience pain relief after 3 months, many experience discomfort or more severe pain several years after hernia repair. The fairly wide range of reported rates of discomfort and pain, ranging from 0% to over 50%, reflects the different postoperative time intervals at which measurements are taken and the different assessment methods. It is unknown to what extent these changes in the frequency of pain reports can be attributed to the combination of prolonged convalescence after surgery and recurrence of pain that occurred after a relatively pain-free postoperative period.

A study conducted by S. Smeds et al. in 2009 [9], describes the variation in postoperative outcomes during the first 2.5 years after surgery, focusing on patients without pain, with moderate and severe pain within 3 months after surgery. The operations were performed by the authors in a day hospital, under general intravenous anesthesia and artificial ventilation. Approximately 80% of all operations were performed by a single surgeon. All patients received the same written and oral information about all stages of surgery and preoperative premedication. Postoperatively, local anesthetics were administered as part of standard postoperative pain management (paracetamol/acetaminophen and dexibuprofen) if necessary. Two cohorts of patients were assessed: those who underwent surgery for primary hernias in March–October 2004, and those who underwent surgery during the same months in 2005. Patients rated the degree of groin pain they experienced through the use of bags visual analogue scales (VAS). A score of 1 reflects the most severe pain imaginable, and a score of 10 indicates no pain. The same VAS scale was used to assess the condition of all patients both before and after surgery. In each cohort, patients were divided into 3 groups according to their pain level 3 months after surgery: those with no pain at all (Group A), those with moderate pain (Group B), and those with severe pain (Group C). The absence of pain corresponded to a VAS score of 10 points, moderate pain - 7-9 points, and severe pain - 1-6 points. In November 2006 (i.e., 12–18 months after surgery in the 2005 cohort and 24–32 months after surgery in the 2004 cohort), patients in group B (moderate pain) were sent a questionnaire asking report the degree of pain experienced using your VAS. The same questionnaire was sent to 79 patients in group A (no pain). These patients were randomly selected - 40 patients from the 2004 cohort and 39 from the 2005 cohort. Patients in group C (severe pain) also received this questionnaire. As a result, a total of 564 patients who underwent primary hernia surgery in 2004 and 2005 were included in the study. Of these, 272 were from the 2004 cohort and 292 from the 2005 cohort. The cohorts were nearly identical in patient characteristics such as sex, bilateral hernias, type of hernia, and preoperative pain scores. Of the total number of patients included in the study (n=564), 464 (82%) were pain-free at 3 months (group A). Group B (moderate pain) contained 42/272 (15%) patients from the 2004 cohort and 49/292 (17%) patients from the 2005 cohort. Of the 2 cohorts (n=564), a total of 9 (1.6 %) of patients reported severe pain (group C). Due to the small number of patients with severe pain in group C, similar patients from the other 2 groups were combined and analyzed as one group. A total of 179 questionnaires were received in November 2007. The response rate in cohort A was 31/39 (79%) and 39/40 (98%) in the 2004 and 2005 cohorts. respectively.

In Cohort B, response rates were 39/42 (93%) and 41/49 (84%) in the 2004 and 2005 cohorts, respectively. All nine patients with severe pain returned the questionnaires. Of the patients in Group A (pain-free 3 months after surgery) who agreed to participate in the survey (n=71), recurrence of pain with a VAS score of 7–9 was reported by 11/39 (28%) in the 2005 cohort. (1-1.5 years after surgery) and 7/31 (23%) in the 2004 cohort (2-2.5 years after surgery). No patient reported severe pain (VAS score 1–6). Of the patients in group B (moderate pain 3 months after surgery), 80 people agreed to take part in the survey. No discomfort was reported by 16/41 (39%) patients in the 2005 cohort (1–1.5 years postoperatively) and 19/39 (49%) patients in the 2004 cohort (2–2.5 years postoperatively) ). The total number of patients who reported any or no pain relief was 20/41 (49%) in the 2005 cohort and 27/39 (69%) in the 2004 cohort. VAS pain increased to 1 -6 points were reported by 9/41 (22%) patients in the 2005 cohort and 6/39 (15%) patients in the 2004 cohort. Clinically significant relapses were found in 3 of 15 patients who reported increased pain from 3 th month after surgery. In Group C, all 9 patients returned their questionnaires and all reported pain relief without using the VAS. However, only 1 patient was pain-free at the end of the study period and 1 patient still reported severe pain.

This single-center observational study showed variability in self-reported postoperative pain during the first 32 months after hernia repair. Homogeneous patient populations in two cohorts (2004 and 2005) allowed comparison of changes in self-reported pain scores over time. It was also quite important to study pain over a long period of time after hernia repair, since it is unknown how self-assessment of pain will change in patients with different intensities of postoperative pain. Three groups of patients with randomly selected self-reported VAS pain levels were analyzed at 3 postoperative periods, namely 3 months (when postoperative pain is defined as chronic), 12–18 months (first year), and 24-32 months (second year) after surgery. This was of great clinical significance, since chronic pain may indicate the continuation of a problem for an indefinite amount of time, which does not appear to be either a late resolution or a late reappearance of postoperative pain. It was also important to examine how pain progressed over 3 months to form the basis for individual patient information and postoperative follow-up. The design of this study allowed us to analyze two time periods after surgery and focus on the relatively small number of patients who reported postoperative pain at 3 months after surgery. In addition, a large number of surgeries were performed in the same clinic using identical procedures before, during, and after surgery. However, 80% of all surgeries were performed by a single surgeon, ensuring consistency in surgical procedures and limiting the potential risk of differences in patient reports of pain resulting from surgery. Three different hernia repair techniques were used because patients were selected based on when the surgery was performed rather than on the specific type of surgery they needed. The study design did not take into account the effect of different herniorrhaphy techniques on postoperative pain scores. The researchers' primary focus was on changes in pain levels after surgery, rather than on the effects of different hernia repair techniques on them. It was found that some patients who did not experience pain 3 months after surgery subsequently reported pain 1 and 2 years after surgery. Most patients with moderate pain at 3 months reported gradual improvement at 1 and 2 years after surgery. However, some patients reported increased pain. Thus, patients with moderate pain experienced both improvement and deterioration. Therefore, during the first 2 years of the postoperative period after open hernia repair, there will be a clear risk of developing postoperative pain, and a patient with moderate to severe pain 1 and 2 years after surgery may fall into the slow-resolving pain group or the pain recurrence group.

This dualism of negative and positive dynamics of postoperative pain after hernia repair points to the problem of identifying a clinically significant time for defining chronic postoperative pain. Pain assessment at two time points after surgery can be done both by patients whose healing process is slow and by patients with recurrent pain. This study showed that at a time point later than 3 months after surgery, such as during the first year after surgery, a single point postoperative pain assessment added a number of patients who initially did not experience pain and reduced the number of slow-to-recover patients with monthly chronic pain.

The cause of discomfort or recurrent pain is unknown. This may be due to the recurrent function of various sensory nerves that were damaged during surgery, similar to the return of vocal function after recurrent nerve injury during thyroid surgery. Alternatively, it may be the result of connective tissue growing into the mesh or the body's reaction to a foreign object. It is interesting that none of the initially pain-free patients who later reported pain rated their pain as severe on the VAS, in contrast to a number of patients who initially had moderate pain for 3 months and then reported pain. more severe pain. However, moderate pain at 3 months after surgery indicates a risk of developing more severe complications within 2 years, in contrast to the group of patients who initially did not experience pain and then began to experience moderate pain. The presence of severe pain within 3 months after surgery carries a more serious clinical significance, since these patients were not free of pain during the 2-year follow-up period (except for one), and that worsening moderate to severe pain correlates with recurrence of hernias . The proportion of patients with severe pain who did not experience pain recurrence (2.5%) is comparable to the relative number of patients with severe pain (3.6%).

All efforts of surgeons should be aimed at understanding the causes of this problem in such patients. In addition to the reduction in their quality of life, they incur additional costs due to treatment of causalgia in clinics and the need for another operation. In conclusion, the authors indicated that postoperative pain after open hernioplasty can either proceed with negative dynamics or appear in the period from 3 months to 2 years after surgery. The study also found that patients with moderate pain were at risk of developing severe postoperative pain syndromes, which was not observed in patients who initially experienced no pain but later experienced moderate pain. Finally, most patients with severe postoperative pain at 3 months after surgery do not experience complete pain relief within the first 2 years after surgery [9].

The problem of the definition and terminology of causalgia, as well as the main postulates in its etiology and prevention deserves special attention. In 2008, an International Conference was held in Rome, which included more than 200 participants and among them were 9 international experts in the field of hernia treatment. At the end of the conference, guidelines for the prevention and treatment of chronic postoperative pain after hernioplasty were presented, and a uniform terminology and definition of postherniorrhaphic inguinal causalgia was created.

In order to analyze the phenomenon of causalgia and attempt to develop practical recommendations for the scientific community, a working group of 9 international experts was created in 2007, selected on the basis of their experience and lists of their publications on this problem. This group set itself 6 main questions with 23 sections regarding postoperative causalgia. A meeting on these issues was held in Rome on April 21-22, 2008. The conference was organized in 2 parts: the first was a closed session reserved for a working group that tried to reach a consensus on each of the 6 issues studied during the previous year. The second session was open to an international audience and was held in the format of a discussion of the conclusions of the expert group. As a result, a number of provisions were formulated.

1. The incidence of debilitating chronic pain after any form of open or laparoscopic hernia repair affecting normal daily activities or work ranges from 0.5 to 6%.

2. Pain after herniorrhaphy was defined as pain due to direct nerve damage occurring in patients who did not report groin pain before surgery. Or, if pain did occur, the postoperative pain was significantly different from the preoperative pain. The working group proposed to include in this definition only chronic pain that occurs from 3 months after surgery and lasts more than 6 months after surgery.

3. The clinical diagnosis of neuropathic pain cannot be determined at this time.

4. Manipulation of the inguinal nerves during hernia repair should be described in the surgical protocol using the following terminology:

— crossing a nerve means interrupting the course of the nerve fiber;

- nerve resection, or neurectomy, means excision of a segment of nerve along the inguinal canal.

5. The results of a survey of an international audience showed that during hernioplasty the identification of the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric and genital branches of the genital femoral nerve seems possible only in 40% of cases. However, the working group, on the contrary, in accordance with international literature, believes that it is possible to identify all 3 branches as separate nerves in 70-90% of patients.

6. Recommendations have been made by both the working group and the international audience to identify and preserve all 3 inguinal nerves because current literature suggests that this reduces the risk of postoperative chronic pain. However, if the nerve was damaged during the operation, or at least there is a suspicion of this, it is unanimously recommended to completely remove it, but it is considered unacceptable to simply excise part of the nerve, leaving its stumps in the surgical field.

7. There was no consensus on the effect of suture glue on the intensity of chronic pain.

8. The working group recommended triple neurectomy if treatment of chronic postoperative pain is ineffective for more than one year [10].

As can be seen from the results of the conference, special attention was paid to the problem of the involvement of inguinal nerves in the etiology of causalgia. Against the backdrop of interest in this fact, in 2010, a study was carried out to study the problem of neuritis during hernioplasty. In 90 patients, 100 inguinal hernioplasties were performed, during which 34 cases of nerve trunk damage were suspected. The experimental audience consisted primarily of Caucasian men aged 25 to 35 years with no known history of spinal deformity, and 3 women with a history of open hysterectomy.

A total of 84 nerves were removed (73 ilioinguinal, 9 femorogenital, 2 iliohypogastric) for various reasons. In other words, in 34% of all hernioplasties in these patients, cases of inguinal neuritis were recorded. Of these, neuritis of the ilioinguinal nerves was present in 30 (88%) of 34 cases, the highest incidence among the three nerves. The locations of neuritis were the area of the nerve passing through the external oblique muscle of the abdomen (83%), the area of the distal bifurcation of the nerve (11%), the area of trifurcation of the nerve (3%), and Hesselbach's triangle (3%). One nerve, suspected of having neuritis, was later found to be normal based on the results of histological examination. Thus, cases of neuritis were accurately identified by the surgeon in 33 out of 34 cases. In the case of pantalal hernias, the incidence of neuritis was 47%, which is higher than the incidence among indirect and direct hernias (32 and 30%, respectively). Inguinal neuritis on the left side of the body occurred 2 times more often than on the right. Thus, it can be stated that the incidence of neuritis of the inguinal nerves ranges from 30 to 46%. These findings have not previously been described in the scientific literature and may represent a paradigm shift in the understanding of preoperative and postoperative pain in inguinal hernias. The method of performing hernioplasty according to Lichtenstein is associated with 12% of all cases of postherniorrhaphic casualgia and a high frequency of intersection of the inguinal nerves during surgery, as well as the adjacency of the 3 nerves described above to the implant. Attempts to reduce the frequency of causalgia during the Lichtenstein operation led all authors to the need to recommend standard lysis of the ilioinguinal nerve for this hernioplasty. Two authors conducted a prospective randomized study, which allowed one of them to reduce the incidence of pain from 28 to 8%, and the other from 21 to 6%. The third author conducted a retrospective study, which reduced the percentage of pain from 26 to 3%. However, other series of studies showed neither improvement nor worsening of results. This suggests that lysis of the ilioinguinal nerve does not cause significant harm [11].

S. Alfieri et al. [12] in a prospective multicenter study showed that the incidence of postoperative pain when all 3 nerves are removed reaches 40%, and this indicates the principle “more is not better.” In light of these studies, the incidence of iliofemoral neuritis indicates that removal of the ilioinguinal nerve is justified in these cases.

Subsequently, many studies were carried out, the purpose of which was to identify the connection between the presence of the synthetic implant itself and the phenomenon of causalgia after hernioplasty.

M. Bay-Nielsen et al. [13] reported a 37% incidence of chronic pain after inguinal hernioplasty. They reported no differences regarding hernia types, surgical techniques, or types of anesthesia.

However, despite the fact that S. Heise et al. [7] introduced the term “mesh inguinodynia” in 1998, they still doubted whether implants really cause pain syndromes or, on the contrary, help eliminate them. The authors conducted their study on 117 reoperated patients. Of these, 20 underwent primary allohernioplasty and 3 underwent laparoscopic surgery. Two patients required mesh removal 1 and 2 years after surgery, 16 patients required mesh removal in combination with removal of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. Patients who underwent mesh removal and neurectomy had a higher rate of excellent results (62%) than patients who underwent mesh removal alone (50%) [7].

Over the past 5 years, a nationwide analysis of complications associated with inguinal hernia surgery has been carried out in Finland, which included an analysis of the results of 55,000 hernia repairs. Open allohernioplasty has been the most common operation over the past 5 years. According to the study results, 2/3 of postoperative complications were associated with chronic pain and infection. The majority of those examined were patients whose work involved significant physical activity and pensioners. The incidence of complications with Lichtenstein hernioplasty was 3.9% lower than with other techniques. It was concluded that chronic pain developed postoperatively in 33% of patients who underwent open hernia repair and 20% of patients who underwent laparoscopic hernia repair. Surprisingly, 47% of patients ended up with chronic neuropathic pain. The study found that mesh implantation caused pain 7 times more often than surgery using patients' own tissue. This group of Finnish researchers used 24 different types of implants, including light, heavy and partially absorbable. Similar complication rates were observed for each mesh subtype.

In addition, as part of the same study, it was determined that the causes of causalgia in the postoperative period include general anesthesia, long duration of surgery, wound infection and bleeding. Surgeries to remove the implant and orchiotomy did not eliminate causalgia. Most complications were associated with primary planned hernioplasty and the open method of performing it. In this study, the greatest number of complications was observed after laparoscopic hernia repair. No specific types of mesh were the main causes of pain. The researchers concluded that mesh implants do not increase the incidence of chronic pain, but the prevalence of factors influencing the occurrence of chronic pain such as preoperative pain levels, age under 40 years, pain in other locations (eg, back), psychosocial disorders, and also heavy physical labor in the work history was increased [14].

A study conducted by U. Fränneby et al. [15], showed that laparoscopic hernioplasty causes causalgia both immediately after surgery and in the long-term period. The methods of Shouldis, Lichtenstein and other types of hernioplasty gave very similar results. These results generally indicate that the mesh implant does not cause an increase in the incidence or intensity of chronic pain in the postoperative period.

Another group of foreign authors [16] concluded that high levels of postoperative pain were present in patients who experienced severe pain in the 1st week after surgery. In addition, similarly high rates of chronic pain were observed in patients who had a recurrent hernia and in patients who had very severe pain before surgery. These investigators concluded that chronic pain occurs less frequently after open and laparoscopic allohernioplasties compared with hernia repairs using the patient's own tissue.

S. Nienhuijs et al. [17] identified risk factors for the development of chronic postoperative pain as young age (<40 years), the patient's fear of pain before surgery, and the fact that regional anesthesia reduced pain levels only during the first day after surgery. The same group of researchers concluded that only 11% of patients undergoing inguinal hernia surgery developed chronic pain, and 3% of patients had moderate to severe neuropathic pain.

H. Paajanen [18] in one of his studies paid great attention to the fact that chronic pain was less common after open and laparoscopic allohernioplasties, compared to operations without the use of meshes. It also confirmed similar findings by other researchers regarding the list of factors that determine chronic causalgia. These included general anesthesia and postoperative bleeding. Subsequently, the author proved that lightweight meshes are less likely to cause postoperative pain; cause a higher relapse rate; improve sexual function (compared to other types of meshes) [18].

M. Kalliomäki et al. [19] reviewed the results of hernioplasty performed on 2834 patients and identified the following factors for increasing postoperative pain: open method of surgery; presence of preoperative pain; a period of less than 3 years since the last operation; type of surgical procedure; the surgeon’s experience, as well as the presence of various postoperative complications. This group of researchers strongly stated that the use of synthetic mesh reduces the risk of hernia recurrence and chronic pain [19].

Based on the problem of the etiology of postoperative causalgia, attention should be paid to the results of a study of the technique of non-fixation allohernioplasty by M. García Ureña et al. [20], who in 2011 tested a new self-fixing polypropylene mesh made from lightweight materials. 10 medical centers took part in the study. Only patients with primary uncomplicated hernias were included in the study. The mesh was placed according to the Lichtenstein technique without any fixation. Patients were surveyed in the 1st week, as well as in the 1st, 3rd and 6th months of the postoperative period. The main purpose of the study was to assess maximum pain in the postoperative period, after 6 months. Pain was assessed using the VAS. A total of 256 patients were operated on. The average duration of the operation was 35.6 minutes, 76.2% of patients were operated on on an outpatient basis. The results included several types of postoperative complications: wound infections in 2%, seromas in 17%, hematomas in 21%, orchitis in 6%. Acute causalgia was observed in 27.3% of cases in the 1st week and 7.5% in the 1st month of the postoperative period, chronic causalgia was observed in 3.6% of cases in the 3rd month and in 2.8% at 6th month. There were no relapses or long-term complications. The study authors concluded that this type of mesh implant can be successfully and safely used in cases of primary uncomplicated inguinal hernias. In addition, in most cases, hernioplasty using self-locking implants can be performed on an outpatient basis. The presence of chronic causalgia was recorded in less than 3% of cases [20].

According to J. Mazin [6], there is currently no definitive answer to the question of the effect of a mesh implant on the incidence of causalgia, since the data are too contradictory. Another issue discussed by the author was the origin or mechanism of mesh-related pain. 5 main factors causing pain were identified: 1) meshes made of heavy materials; 2) the individual process of postoperative scar formation for each patient; 3) a situation in which the surgeon pays insufficient attention to the technical details of mesh implantation; 4) allergic reactions to mesh materials such as polypropylene and polyester; 5) direct or indirect nerve damage or inflammation of surrounding nerves.

Thus, J. Mazin [6] identifies the main recommendations for reducing the possibility of postoperative causalgia. He strongly recommends the use of lightweight meshes for hernioplasty. For the option using laparoscopic technology to perform the operation, it is recommended to use non-fixation methods for implant placement. As part of standard technique, any sutures or staples should be placed only with direct visualization, coupled with precision and awareness of the surrounding anatomy, especially nerves. It is important to determine the patient’s individual sensitivity to a particular synthetic material. Continuous attention to technical and anatomical details during surgery is of paramount importance. The surgeon should avoid placing mesh in areas of known defective tissue. This refers to infected or inflamed tissue. Finally, the surgeon must tailor the procedure to the individual patient, rather than the patient to the procedure. In hernia surgery, the same technical procedures cannot be used on all patients. Different patients require different surgical techniques and different types of implants. Using the same technical approach for all patients is a significant reason for the occurrence of postoperative causalgia [6].

The analysis of literature data allows us to formulate several provisions:

— the anatomy of the groin region remains very complex, and the groin region itself is one of the most difficult anatomical areas of the human body to navigate during surgery;

— the surgeon’s exceptional attention to the smallest details of surgical technique and anatomical features is the key to a positive result of surgical treatment of hernias;

— precise individual choice of hernioplasty technique (of course, with some standardization) should be made for each patient;

— at present, there is no “gold standard” technique for inguinal hernioplasty that would prevent the development of causalgia in the patient, as well as an “ideal” implant and a technique for fixing the latter.

How to care for a wound when the stitches are removed after surgery?

It would be useful to remind you that stitches should only be removed by a specialist - a doctor or nurse. It is strictly forbidden to perform this procedure yourself, due to the high risk of causing infection in the wound or causing bleeding.

Treatment of the incision site after removal of the sutures is carried out using the same means as before. Treatment procedures last until the wound is completely healed. This usually takes about 1 week.

Professional care for postoperative sutures at Stoletnik MC

If in any matters related to taking care of your own health, you prefer to trust professionals, you are welcome at the medical office. To help those who are not sure how to properly care for a suture after surgery, a wide range of post-operative services is available. Among them:

- dressing large and small;

- removal of stitches up to 5 cm;

- removal of sutures 5–10 cm;

- removal of stitches more than 10 cm;

- sanitation of the wound surface;

- scar excision;

- and much more.

The responsibility and high professionalism of the clinic’s staff is the key to the safe and speedy recovery of our patients. And the affordability of the services provided will eliminate the need to waste time and nerves on trips to the clinic. Sign up for procedures by phone: +7 (8412) 999-395, 76-44-20. We are waiting for you at the address: Penza, st. Chaadaeva, 95 (Shuist microdistrict).

Literature

- Belyaev A.N., Kozlov S.A., Taratykov I.B., Novikov E.I. Patient care in a surgical clinic: textbook. allowance. – Saransk: Mordovian University Publishing House, 2003. – 136 p.

- Buyanov V. M. Egiev V. N. Udotov O. A. Surgical suture. – M.: Antis, 2000. – 92 p.

- Zoltan J. Operating technique and conditions for optimal wound healing. – Budapest: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of Hungary, 1983. – 175 p.

- Mironova E. N. Fundamentals of physical rehabilitation. – M.: MOO “Academy of Safety and Survival”, 2016 – 310 p.

- Semenov G.M., Petrishin V.L., Kovshova M.V. Surgical suture - St. Petersburg: Peter, 2001. - 256 p.

Author: Korolev E. S.

Reviewer: reflexologist Kurus A. N.