Congenital malformations of the skin and subcutaneous fat

Congenital malformations of the skin and subcutaneous fat in children have various forms of manifestation.

One of them is nevus. This is a neoplasm that appears as a result of a high concentration of nevocytes in a certain area of the skin. Normally, skin color is formed by melanocytes distributed in equal density. However, pathology may develop, due to which melanocytes degenerate into nevocytes, which, through their accumulation, form a pigmented nevus in a child. It can occur during pregnancy or appear shortly after birth.

To one degree or another, the following factors can lead to the development of pathology:

- gene breakdown;

- the presence of a genitourinary infection in the mother during pregnancy;

- heredity;

- the impact of negative external factors on the mother’s body during pregnancy;

- incorrect diet of the mother during pregnancy, the predominance of artificial colors, preservatives, and flavors;

- long-term use of hormonal contraceptives before pregnancy.

Initially, pigmented nevus in children is defined as a benign formation. However, it may have melanocytic activity, which means it can grow. As the child ages, not only the spots may grow, but also the appearance of new ones, as well as their degeneration into malignant tumors. A skin tumor - melanoma - is aggressive, as it quickly progresses and metastasizes to nearby organs and tissues.

Pigmented nevus is detected in approximately 1% of children.

Boys and girls are equally susceptible to the appearance of spots on the skin. A nevus can look different: a medium or large-sized nodule, a spot colored differently from the main skin tone, a wart. Localization is also varied: limbs, torso, head. In most cases, nevus occurs on the child's head, neck, chest or upper back.

The size of the formations varies from several mm to several cm. In approximately 5%, the number of nevi is so large that they occupy a significant proportion of the skin surface. Normally, when palpated, they can be both soft and nodular, but without pain.

Congenital melanocytic nevus - symptoms and treatment

For congenital nevi, surgical and drug treatment, laser therapy and other methods are used.

Surgery

Large nevi are recommended to be removed in early childhood - this will help avoid emotional and behavioral disorders in the child. Such children, due to external differences, may consider themselves inferior to others and avoid their peers. In addition, they may face bullying from other children.

However, not all nevi can be completely removed. If they occupy a large area and the defect cannot be closed with healthy tissue, then the operation is not performed, or the nevus areas are partially excised.

The extent of the operation depends on the location of the nevus and the depth of the lesion. Its necessity for large and giant nevi is considered controversial. Many experts suggest removing the most heterogeneous, thick or coarse areas of the nevus, which complicate clinical observation [45][46]. Often the best choice is to closely monitor the nevus without undergoing surgery.

The only absolute indication for surgical treatment is the development of a malignant tumor in the lesion. But even with complete excision of large and giant nevi, the risk of oncology remains, since melanocytes can penetrate deep-lying tissues: muscles, bones and the nervous system.

The following complications may occur after surgery: contractures, seromas, hematomas, soft tissue infections, skin flap ischemia, suture dehiscence, and keloid scar formation. Hematomas, seromas and ischemia of the flaps appear immediately after surgery, keloid scars form later, on average during the first year.

Other treatments

The external defect can be reduced using curettage, dermabrasion and laser therapy. The methods are more effective in early childhood, since nevus cells in a child are located in the upper layers of the skin [21][22]. After the procedures, these cells remain in the dermis and over time the pigmentation partially returns. In some cases, melanoma develops in such areas, but the relationship with the treatment has not been proven [23][24][25][26][27].

Contraindications for these procedures are individual. As a rule, these include local disorders: ulceration, cracking, peeling, nodules, tissue immobility and bleeding.

Medical examinations after surgery

Regardless of the treatment performed, patients with large congenital nevi need to undergo a medical and dermatological examination once a year. It is also necessary to palpate the nevus and scars that arise after its removal. If nodules or other suspicious lumps are detected, a histological examination, i.e., examination of tissue samples, is indicated.

Types of nevi

The spots have clear boundaries and color from pale brown to black.

Small and medium-sized formations, due to their light tone, can be practically indistinguishable in the first 2-3 months after the birth of the child. However, as they grow, they darken and grow proportionally in size. Nevi can also be non-pigmented, then they can be identified by touch by the different structure of the skin.

Spots are divided by size into:

- small - up to 1.6 mm;

- medium - from 1.6 to 10 mm;

- large - from 10 to 20 cm;

- giant - from 20 cm.

Another criterion for classification is clinical type. According to it, nevi are:

- Adenomatous. They are located on the face and head, have a convex shape, clear boundaries, and the color varies from yellowish to dark brown.

- Warty. Located on the torso or limbs. They are characterized by uneven outlines and surface, dark color.

- Giant pigment ones. They often develop in utero and can be located on one or both sides of the body. The surface is covered with hairs, often accompanied by a scattering of small neoplasms around them.

- Blue. They are located in the upper body, on the face and hands. The color is bluish or gray-blue, the surface is dense and glossy. The nevus protrudes slightly above the surface of the skin and does not exceed 2 cm in diameter.

- Papillomatous. They are located on the head and do not have clear boundaries or outlines. The surface is heterogeneous, the color ranges from light to almost black. When injured, it becomes inflamed.

- Epidermal. They are usually located on the limbs one at a time. They have an uneven surface and color from light to dark.

A characteristic sign of a non-malignant neoplasm is the presence of hairs on the surface.

Helpful information

INFANTILE (INFANT) HEMANGIOMA

Infantile hemangioma is a benign vascular tumor that develops from endothelial tissue. It is characterized by the following periods of development:

- proliferation (growth) up to 6-8 months. child's age

- stabilization 8 – 12 months

- involution (regression) up to 5 – 10 years.

Diagnosis of infantile hemangiomas:

- Superficial infantile hemangiomas do not require special diagnostic measures, since they are diagnosed according to a specific clinical picture, however, to diagnose complex forms of hemangiomas (subcutaneous, combined, segmental), additional ultrasound examination with Dopplerography may be required to determine the nature of the blood flow, the volume of the subcutaneous part of the hemangioma and the presence feeding vessel(s). In some cases, an MRI or CT scan with contrast may be required (a CT scan without contrast is not informative)

Treatment of hemangiomas in children:

- conservative treatment: systemic therapy with beta-blockers, local lotions - the most modern, gentle method with a minimal likelihood of side effects, provided that parents strictly follow the doctor’s recommendations

- wait-and-see tactics

- cryodestruction – performed according to indications for small hemangiomas

- sclerotherapy – most effective against vascular and lymphatic malformations

- laser treatment – cosmetic removal of residual elements, telangiectasias.

- Close-focus X-ray therapy is one of the most outdated methods and is not recommended due to the large number of serious, irreversible side effects

- surgical treatment - indicated in the case of complex forms of large hemangiomas when drug treatment is ineffective

- steroid hormones – has a large number of side effects, can be used extremely rarely if other treatment methods are ineffective

- vincristine for kaposiform hemendothelioma, Kasabach-Merritt syndrome - segmental infantile hemangioma in combination with thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy

Treatment of infantile hemangioma with beta blockers:

- In 2008, the French doctor Lehaute-Labrese discovered the effect of propranolol on infant hemangiomas. Given the low risk of side effects and high effectiveness of treatment, beta-blocker therapy has become the “first line” in the treatment of IH. The exact mechanism of action of beta-blockers on IH is still unknown. The proposed mechanism is vasoconstriction, inhibition of angiogenesis, and stimulation of apoptosis.

- Therapy with beta-blockers can be carried out both locally, in the form of lotions, and systemically.

The treatment method is selected taking into account each specific clinical case, the type of hemangioma and its location, and the wishes of the parents are also taken into account.

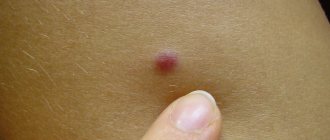

PYOGENIC GRANULOMA

The formation, consisting of vascular tissue, is not of true bacterial origin and is not a true granuloma. Granuloma develops rapidly, often at the site of a recent injury (although the patient may not remember the injury), is usually less than 2 cm in diameter and may be a vascular or fibrotic reaction to injury. Education occurs with equal frequency in men and women of different ages.

The epidermis covering the formation is thin, and the formation is fragile, bleeds easily and does not fade when pressed. The base may be pedunculated and may be surrounded by a rim of epidermis.

NEVUS OF UNNA

Nevus of Unna is a red birthmark on the skin of the face, back of the head and neck in newborns. Causes: expansion of capillaries on the scalp. Do not confuse nevus of Unna and hemangioma.

Symptoms:

- A pink or red spot on the skin of the nose, bridge of the nose, forehead, eyelids, neck and back of the head

- The spot is flat, does not rise above the skin, when pressed with a finger, the spot turns pale, parents note that when the child is restless and crying, the spot becomes brighter

- Treatment is not required, it goes away on its own by the age of 1-2 years, if with age, after 3-5 years, residual elements remain, laser correction with a vascular laser is possible.

Methods for treating nevi

Treatment is allowed only in patients over 2 years of age. Therapy has 4 main directions:

- surgical removal;

- laser excision;

- cryodestruction;

- electrocoagulation.

As a rule, nevi that have grown deeply into the tissue are surgically removed. Giant neoplasms are removed in several stages, but the disadvantage of this method is the formation of scars at the site of the nevi.

Laser coagulation is used to remove dysplastic pigmented nevi and other clinical types of spots. The method allows removal of the formation without pain and without subsequent scarring.

Cryodestruction involves exposing the affected area of skin to very low temperatures. As a result, the altered cells die and are replaced by healthy ones. After cryodestruction, a small crust appears, which quickly disappears.

Electrocoagulation affects the nevus with high temperatures. Typically this method is used to remove small and medium-sized stains.

Types of epidermal nevi

There are several clinical types of epidermal nevi. This classification is not definitive, since epidermal moles can be hard, linear and inflamed at the same time.

Soft papillary nevus of the epidermis . This is most often a small flesh-colored or gray formation with a soft, velvety surface. Individual papules forming clusters resemble senile warts.

Hard papillary nevus.

Unilateral, segmented, most often located on the trunk and limbs. These are tall or flat, raised discolorations of normal skin, light or dark brown, with a papillary surface.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus.

This is a special form of epidermal nevus with inflammation and severe itching. ILVEN may worsen and disappear, especially in the form of psoriasis-like psoriasis.

According to the conclusions of the study. Altman and Mehregan, diagnostic criteria for such moles include a number of features:

- early onset is noted - in 75% of cases before 5 years,

- more common in females (4 times more often);

- frequent localization on the left lower limb and buttocks;

- itching is usually present;

- histopathological appearance resembling psoriasis - a characteristic pattern of parakeratotic areas with visible psoriasis-like epidermal hyperplasia, mild spongy edema and exocytosis of lymphocytes;

- Such nevi have no tendency to spontaneous regression and resistance to treatment.

The lesions are linear, pruritic, erythematous lesions with a flaking surface and may resemble psoriasis lesions with a linear pattern. They are distinguished from psoriasis by the absence of Munroe microcirculation and the lack of epidermal involucrin expression in ILVEN. The connection with psoriasis is confirmed by the participation of the cytokines IL-6, IL-1, TNF-alpha, ICAM-1 in the pathogenesis.

Horny nevus (nevus corniculatus)

. This is the rarest form of epidermal nevus. The clinical picture shows very intense keratosis with the formation of thick papillary growths and filamentous formations. Histopathological examination shows foci of acantholysis with depressions in the epidermis filled with dense keratin.

Pediatric epidermal nevus.

This variety is characterized by congenital hemidysplasia, unilateral ichthyosis and limb defects. All of these disorders can occur, but it can only be the cutaneous form. The lesions are located unilaterally and do not extend beyond the midline of the body, with the most common lesions being the flexor folds. They have the character of erythematous lesions covered with yellow hyperkeratotic scales and sometimes with horny plugs. This type of mole occurs only in women because the gene responsible for the condition is located on the X chromosome.

Epidermal nevus syndrome, which is a combination of epidermal nevus with other developmental defects, has been clinically identified.

There are 4 clinical variants of the syndrome (Michalovsky classification):

- four-symptom form - lesions of the skin, bones, nerves and eyes.

- three-symptomatic form - skin, bone and nervous changes.

- two-symptomatic form - skin and bone changes.

- monosymptomatic form - the presence of a linear papillary epidermal nevus.

Etiology and pathogenesis of port-wine stains

In most cases, port-wine stains (nevus flaminga) are a birth defect . They are present in the baby immediately after birth and increase in size in proportion to the further growth of the child. An important feature of port-wine stains is the lack of spontaneous regression - they form for a lifetime and, as a rule, have a negative impact on a person’s psychological state.

In rare cases, port-wine stains may appear on apparently healthy skin in adulthood - this is the so-called acquired capillary angiodysplasia . Sometimes port-wine stains may not be an independent pathology, but signs of severe syndromes: Sturge-Weber (encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis with damage to the pia mater) or Klippel-Trenaunay (vein malformations with hypertrophy of bones and soft tissues).

The International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classifies capillary angiodysplasia according to the predominant vessel type—arterial, venous, lymphatic, capillary, or complex.

Clinical case of progressive dysplastic nevus with transition to melanoma

Romanova O.A., Artemyeva N.G., Solokhina M.G.

CJSC "Central Polyclinic of the Literary Fund", Moscow, Russia

Published

: Journal of Clinical Dermatology and Venereology, 2022, 17(2): 34-37.

An observation of a large dysplastic nevus with transition to melanoma in situ

.

The difficulties in morphologically establishing the diagnosis of melanoma in situ

.

Keywords

: progressive dysplastic nevus, melanoma in situ.

Dysplastic nevi are currently attracting the attention of researchers due to their possible transformation into melanoma. Dysplastic nevi can be multiple or single, hereditary or sporadic. In 1978, Clark et al first described multiple hereditary nevi, which are precursors to melanoma, and designated this situation as “B-K mole syndrome” [1]. Histologically, these lesions, which later became known as dysplastic nevi, consisted of atypical melanocytic hyperplasia, lymphoid infiltration, tender fibroplasia, and new blood vessels. In 1980, Elder and co-authors described similar nevi in patients with non-hereditary melanoma and showed that dysplastic nevus syndrome, like the hereditary “B-K-mol syndrome”, is a risk factor for the development of cutaneous melanoma [2]. In a histological study of dysplastic nevi, the authors found 2 types of growth disorders of intraepidermal melanocytes, the most common type - lentiginous melanocytic dysplasia (LMD) - was observed in all dysplastic formations and resembled the changes occurring in lentigo simplex. A second type of growth disorder, epithelioid cell melanocytic dysplasia, was found in 2 lesions in addition to lentiginous melanocytic dysplasia and resembled classic superficial spreading melanoma. In 1982, professor at the Moscow Research Institute named after. P.A. Herzen Z.V. Golbert [3] was the first to identify 3 degrees of development of lentiginous melanocytic dysplasia (LMD). At grade 1, there was an increase in the number of melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis and some atypia. At grade 2, there was a more pronounced proliferation of melanocytes, in some places completely replacing the basal row of keratinocytes, and an increase in signs of their anaplasia. Stage 3 LMD, in which there is a tendency for melanocytes to grow into the upper layers of the epidermis and deeper into the papillary layer of the dermis, approaches the picture of melanoma in situ

.

The possible development of melanoma against the background of a nevus has been noted by many authors. N.N. Trapeznikov, in his 1976 monograph, cites data from foreign authors who in 1971-1973 noted accumulations of pathologically altered melanocytes in borderline nevi [4]. N.N. Trapeznikov and co-authors also believed that borderline nevi can become malignant, and therefore require observation. However, the authors considered symptoms such as weeping and bleeding to be signs of nevus malignancy. These signs are characteristic not of a nevus, but of an already developed melanoma in the horizontal growth phase. The authors clearly underestimated Clark's discovery in 1969 of superficial spreading melanoma, which undergoes a long phase of horizontal growth under the mask of a nevus [5]. Exophytic growth of the formation, which the authors consider a sign of malignancy of the nevus and associate it with trauma, indicates the transition of already developed melanoma from the horizontal growth phase to the vertical one [5]. The main factor in the prognosis of melanoma is currently considered to be the thickness of the tumor, determined in millimeters during histological examination. A good prognosis applies to tumors with a thickness of 1 mm or less. Such a tumor is called “thin melanoma” and clinically appears as a smooth pigmented spot or slightly raised pigmented formation. Exophytic growth indicates that the thickness of the tumor is increasing and indicates a poor prognosis.

Dysplastic nevi can be small - up to 0.3 cm, medium - 0.4-0.8 cm and large - 0.9-1.5 cm; they are pigment spots or slightly raised formations of a reddish or brown color. Unlike ordinary (borderline) nevi, which are found in children, dysplastic nevi appear in adolescence and later in life until old age. Our observations have shown that dysplastic nevi can be either lentiginous or mixed, but they do not turn into intradermal nevi and do not become fibrotic, as happens with borderline nevi in children. Dysplastic nevi are benign formations; they exist for a long time without any changes or regress, but in some cases they can progress to melanoma. The progression of a dysplastic nevus (grade 2-3 dysplasia) may be indicated by an irregular shape, wavy or scalloped edges, and heterogeneous coloring of brown or black tones [6-8]. Dysplastic nevi with grade 1 dysplasia clinically have a regular shape, uniform color, and smooth edges. However, the main sign of a progressive dysplastic nevus, as our observations have shown, is a change in the size, color or configuration of the nevus over the past 6-12 months or 1-10 years. The rapid (within 6-12 months) growth of a nevus that appears on healthy skin after the onset of puberty is an important sign of progression, so such nevi should be subjected to excisional biopsy even in the absence of other clinical signs. The appearance of bluish or pinkish tones in the color of the nevus should be alarming, which may indicate the transition of the nevus to melanoma.

Clinically distinguish progressive dysplastic nevus from melanoma in situ

is not possible, since malignancy occurs at the cellular level. The diagnosis is established only by histological examination, which requires a highly qualified pathologist.

At the Central Clinic of the Literary Fund, we have been performing excision (excisional biopsy) of dysplastic nevi on an outpatient basis since 2009 in order to prevent melanoma [6-8]. Small and medium-sized dysplastic nevi with signs of progression are subject to excisional biopsy. We refer patients with large progressive dysplastic nevi to an oncology hospital, since in these cases it is impossible to exclude superficial spreading melanoma in the horizontal growth phase. Histological examination of these formations, removed in oncology hospitals, revealed melanoma, but in two cases a diagnosis was made - pigmented nevus. We present these observations.

Patient K., 63 years old

, went to the Central Clinic of the Literary Fund on November 6, 2015 about a pigmented spot in the back area, which she noticed 5 years ago, for the last 6 months she has noticed itching in the area of the spot. On examination: in the left scapular region there is a pigment spot of 2.0×1.8 cm, irregular in shape, heterogeneous color of brown and dark brown tones, with areas of bluish-pink color at the upper outer edge. The spot has uneven, scalloped edges (Fig. 1, 2). The axillary lymph nodes are not enlarged. The patient was referred to an oncologist at her place of residence with suspected melanoma. At the Oncological Dispensary No. 4, the lesion was scraped for cytological examination, and melanoma cells were obtained. The patient was sent to City Clinical Hospital No. 5 for surgical treatment. Examination in the hospital: on the skin of the left scapular region there is a formation of 2.0×2.0 cm, black-brown in color, with an uneven surface and uneven scalloped edges, without an exophytic component, with a small crust.

Picture 1

. Progressive dysplastic nevus with transition to melanoma in a 63-year-old woman.

Figure 2

. Progressive dysplastic nevus with transition to melanoma in a 63-year-old woman (close-up).

On 11/25/15, the formation was excised at a distance of 2.0 cm from the visible boundaries. Histological examination No. 82986: in the area of the spot, in the center of the skin flap, there is a picture of epithelioid melanocytic dysplasia of an atypical nature, in one of the areas it is extremely suspicious for the transition to melanoma (?). The patient was discharged from the hospital with a diagnosis of pigmented nevus of the skin of the left scapular region. The histological specimen was consulted at the Moscow Oncology Research Institute named after. P.A. Herzen Ph.D. Yagubova E.A., conclusion: epithelioid cell pigment nonulcerated lentigo melanoma in situ

against the background of a mixed dysplastic nevus, with moderate lymphoid-plasma cell infiltration at the base. Removed within healthy tissue.

In the above observation, the patient had a clear clinical picture of a progressive dysplastic nevus: irregular shape, uneven “scalloped” edges, heterogeneous coloring, the appearance of a spot on healthy skin 5 years ago and its further growth. Due to the presence of areas of pinkish-bluish coloration, skin melanoma was suspected. When scraping the formation at Oncology Dispensary No. 4, it was probably in the area of pinkish-bluish color that melanoma cells were identified. However, it should be noted that we have encountered melanoma in situ

in the presence of a pigment spot with a relatively uniform color. Despite intraepidermal melanocyte dysplasia identified during histological examination, the hospital pathologist did not give a conclusion about the presence of a dysplastic nevus, although it is important for the clinician to obtain such information. Melanocytic dysplasia grade 2-3 indicates a high risk of developing melanoma in this patient. It should be noted that recently some foreign authors have also begun to distinguish 3 degrees of melanocyte dysplasia: mild, moderate and severe.

This observation showed that the diagnosis of “melanoma in situ

"causes difficulties for domestic pathomorphologists.

This may explain the fact that melanoma in situ

is diagnosed extremely rarely in the Russian Federation, while in the USA and Australia it is diagnosed very often.

According to John W. Kelly [9], in Australia from 1996 to 2000, 5117 melanomas were identified, with melanoma in situ

identified in 1711 cases (33.4%).

In 2007, there were 59,940 cases of invasive melanoma and 48,290 cases of in situ

[10].

We present another observation where, in the presence of a typical picture of a progressive dysplastic nevus, the diagnosis was not morphologically confirmed.

Patient P., 50 years old

, contacted an oncologist at the Central Clinic of the Literary Fund on 04/03/15 regarding a pigmented formation on the skin of the back, which he noticed 3 years ago. On examination: in the left scapular region there is a black spot 1.2×0.9 cm, irregular in shape, with uneven edges, in the center there is a small elevation 0.2 cm of light brown color (Fig. 3). The patient was sent to Oncology Hospital No. 40 with suspected melanoma. On 04/13/15, a wide excision of the formation was performed. Histological examination – borderline pigmented nevus.

Figure 3

. Progressive dysplastic nevus in a 50-year-old man.

Considering the clinical picture characteristic of a progressive dysplastic nevus, we, despite the lack of morphological confirmation, informed the patient that he had a high risk of developing melanoma. After 1.5 years, 12/30/16. The patient himself turned to an oncologist at the Central Clinic of the Literary Fund with complaints about the appearance of a pigment spot on the torso 1.5 months ago. On examination, on the back on the left, along the posterior axillary line, there is a spot 0.4×0.3 cm, dark brown, almost black. At the Central Clinic of the Literary Fund, on January 17, 2017, an excisional biopsy of the formation was performed, departing from the boundaries of 0.5 cm. Histological examination was carried out at the Moscow Oncology Research Institute named after. P.A. Herzen (Yagubova E.A.), revealed a mixed pigmented nevus with severe (grade 3) melanocytic leniginous dysplasia, removed within healthy tissue. It is based on pronounced lymphoid-plasma cell infiltration.

The above observations show that for the timely detection of progressive dysplastic nevi and melanoma in situ

it is necessary to improve the qualifications of domestic pathomorphologists.

We consider it advisable to organize advanced training courses for pathomorphologists on the basis of the Moscow Research Institute named after P.A. Herzen, this will contribute to the timely detection of melanoma in situ

and reduce mortality from this dangerous skin tumor.

Literature

- Clark WH, Reimer RR, Greene M, Ainsworth AM, Mastrangelo MJ. Origin of Familial Malignant Melanomas from Heritable Melanocytic Lesions. The BK mole syndrome. Archives of Dermatology, 1978; 114(5): 732-739.

- Elder DE, Leonardi J, Goldman J, Goldman SC, Greene MH, Clark WH. Displastic nevus syndrome. A phenotypic association of sporadic cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1980; 46(8): 1787-1794.

- Golbert Z.V., Chervonnaya L.V., Klepikov V.A., Romanova O.A. Lentiginous melanocytic dysplasia as a precursor to the development of malignant melanoma. Pathology archive. 1982; 12: 36-41.

- Trapeznikov N.N., Raben A.S., Yavorsky V.V., Titiner G.B. Pigmented nevi and skin neoplasms. M., 1976.

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, Mihm MC. The histogenesis and biological behavior of primary human malignant melanoma of skin. Cancer Research. 1969; 29: 705-726.

- Romanova O.A., Artemyeva N.G. Surgical prevention of skin melanoma. Oncosurgery. 2013; 5(3): 12-18.

- Romanova O.A., Artemyeva N.G., Yagubova E.A., Marycheva I.M., Rudakova V.N., Veshchevaylov A.A. Tactics for managing a patient with dysplastic nevus. Clinical dermatology and venereology. 2015; 14(2): 92-97.

- Romanova O.A., Artemyeva N.G., Yagubova E.A., Marycheva I.M., Rudakova V.N., Veshchevailov A.A. Principles of excisional biopsy of dysplastic nevus in an outpatient setting. Oncology. Journal named after P.A. Herzen. 2016; 5(1): 36-41.

- Kelly J. The management of early skin cancer in the 1990s. Austr Fam Physician. 1990; 19: 1714-1729.

- Usatine R.P., Smith M.A., Mayo E.D. and others. Dermatology. Atlas-reference book for practicing physicians. Per. from English M., 2012; 324-335.

How to treat alopecia in children?

The treatment method depends on the cause of alopecia in children, which is determined during the examination. In addition to general therapy, doctors often prescribe additional hair care products (external) and multivitamin complexes. Source: N.V. Pats Treatment of alopecia in children (literature review) // Journal of GrSMU, 2006, No. 3, pp. 8-11

If the baldness is not caused by a serious medical condition that needs to be addressed immediately, a “cure by waiting” may be recommended. In this case, the child is monitored for several months. During this time, the pathology may go away on its own.

Treatment with traditional methods is prohibited. This can aggravate the underlying cause and affect the child's future life.

Therapy should be based on the identified cause of hair loss. In all cases, children are prescribed restorative treatment, which includes:

- immunomodulators;

- phytina;

- vitamins A, E, C, B1, B6, B12;

- methionine;

- pantothenic acid;

- for total alopecia - systemic administration of hormonal drugs.

In the case of the topical type of the disease, ultraviolet irradiation of the foci of hair loss is performed. They are first lubricated with a photosensitizing drug based on amia major, parsnip, and methoxsalene. Darsonvalization of the scalp is also performed.

Every day, the scalp is cooled with chlorethyl, various tinctures and emulsions, and prednisolone-based ointment should be rubbed into it.

If a child has lost hair due to a burn, then new hair will not grow at the site of the scar if conservative therapy is used. Only a skin transplant can help.

Alopecia is psychologically difficult for a child, so he may need the help of a child psychologist.

Sources:

- E.V. Maslova, O.N. Pozdnyakova. Structure and clinical variants of alopecia in the practice of a dermatovenerologist // Journal of Siberian Medical Sciences, 2012, No. 2.

- N. Bekbauova, R. Aliyeva, Zh. Zharasova, O. Stepanova. Etiology of alopecia areata in children // Medical Journal of Western Kazakhstan, 2012, No. 3(35), p.90.

- N.V. Pats. Treatment of alopecia in children (literature review) // Journal of GrSMU, 2006, No. 3, pp. 8-11.

The information in this article is provided for reference purposes and does not replace advice from a qualified professional. Don't self-medicate! At the first signs of illness, you should consult a doctor.